Furs Majeure

Nine years ago Richard Butler moved to New York, leaving London behind. He found England- once the perfect stage for the Psychedelic Furs, a group of amateurs with a few ideas and fewer guitar chords-stifling. Now he lives on St. Mark's Place above the baseball cap and roach-clip street vendors, across from what may be the city's biggest Narcotics Anonymous meeting.

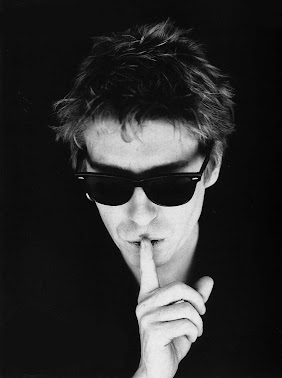

Butler is visiting his brother Tim, the Furs' bassist, who also lives on St. Mark's. Thin and pale, Richard wears tapered black trousers and an old T-shirt. His hands are small, his shoulders slightly rounded, his manner reserved. Never mind that he abandoned the reclusive life of a painter nearly fifteen years ago to voluntarily hold himself up to the scrutiny of the pop audience as an art rocker at that- the man is genuinely shy.

It's not so much that he feels he belongs here, it's just that it's not England. He detests England, and going back there causes him great anxiety. He was recently diagnosed with a heart murmur he says it felt like a flock of butterflies in his chest that he now manages by meditating. Uneasy with himself, he's at ease in America, where he can drive along endless highways, through countryside that looks like a Neil Young song, where his form of alienation sells to the disenfranchised who gather by the new-music bins at suburban record stores. In New York, whether at the Ritz to see the Pixies or at a swank East Side restaurant wearing flared synthetic trousers, he never quite fits in, but he's chosen a city where no one really does.

There's a knock at the door. Butler opens it and peers tentatively out. It's Furs guitarists John Ashton and Knox Chandler. These are Butler's friends, but they treat him with the slightly cautious respect due the oldest boy in the clubhouse. Peggy, Tim's wife, offers to make cocktails. "A bit early for that, isn't it?" Butler teases. He's been sober for nine years. It was nearly a decade ago that the Furs released their second LP, Talk, Talk, Talk, an album that launched a million self-pitying pouts, albeit five years later, when John Hughes wrote a movie inspired by "Pretty in Pink." The Furs didn't get caught in the John Hughes bind as did their peers OMD and Simple Minds maybe because they had more distance from their song (which had nothing to do with a poor girl making her own prom dress) and maybe because they'd already established themselves in the alternative-rock kingdom with such hits as 1984's "The Ghost in You" and "Heaven." "I was flattered," says Butler, "but I thought the movie was a joke. After that our record company said, 'Why don't you write another "Pretty in Pink"? It's ironic. We're not a band that does anything again."

However unconsciously, the Psychedelic Furs are doing it again. On their new record, World Outside, the Furs sound like they did when they first started out in London in the late Psychedelic Furs (left to right): Knox Chandler, Tim Butler, '70s: a New Wave band Richard Butler, Don Yallech, Joe McGinty, and John Ashton. motivated by punk energy, inspired by Bowie and Roxy Music. They were arty, though Butler won't admit it. He thinks that sounds pretentious.

To record World Outside, the Furs went to Woodstock, where they'd done Forever Now with Todd Rundgren in '82. Where Book of Days, their last LP, was musically messy, World Outside is more controlled melody through menacing guitar and exploratory. Butler isn't a storyteller; he's introspective, apparently unaffected by circumstance or environment. If these songs are about anything, they're about personal commitments, varying in nature from love on "Valentine" to addiction on "Until She Comes." They're so honest that Butler, once he heard the completed album, sat in a corner, frightened, feeling exposed.

At a lower-Manhattan gallery, Butler peruses an exhibition of black and white photographs of musicians. He quickly scans each frame, from Hendrix to Vanilla Ice, as if pop music holds no meaning for him. Lingering before an especially good photo of the Rolling Stones, he holds his hand in front of Mick Jagger's face so only the band is visible. "Now," says Butler, "that's a better picture."

It's as if Butler is both fascinated by and contemptuous of his own medium. He is nonplussed by Marianne Faithfull's interest in recording a Furs song, but goes over the top in praise of Michael Stipe. His knowledge of rock is academic; when he makes even a casual reference, he footnotes it. When he looks at a picture of Miles Davis, he remembers how Davis used to perform entire sets with his back to the audience. Butler tried that once; it worked pretty well. Dancing like Bowie and dressing like him also worked. Butler, however, is more a studied impression than a copy. Butler thinks a lot about himself and a lot of himself, but he laughs often and is never smug. He was raised in Surrey with two brothers, a mother, and a father who worked for the British government. He grew up listening to Dylan, Hank Williams, and Edith Piaf. Now, at thirty-six, Butler has found as comfortable a home as he probably ever will, here in New York's East Village. He has settled in a place where he can go buy a black suit if he needs to; where he can go to the corner, get some food, go home and cook it; where he can scribble lyrics and not be interrupted; where he can walk around Astor Place, quietly recognized but respectfully left alone.